TL:DR

Delivering Voyager from Florida to her temporary home in Virgina was epic. I mean nobody died or anything but it very nearly ended the whole idea before we started, the fuel system failed, the batteries failed, the rigging failed. We had (several) groundings, lost an anchor, got towed, had salt water flowing into the hull, you get the picture…

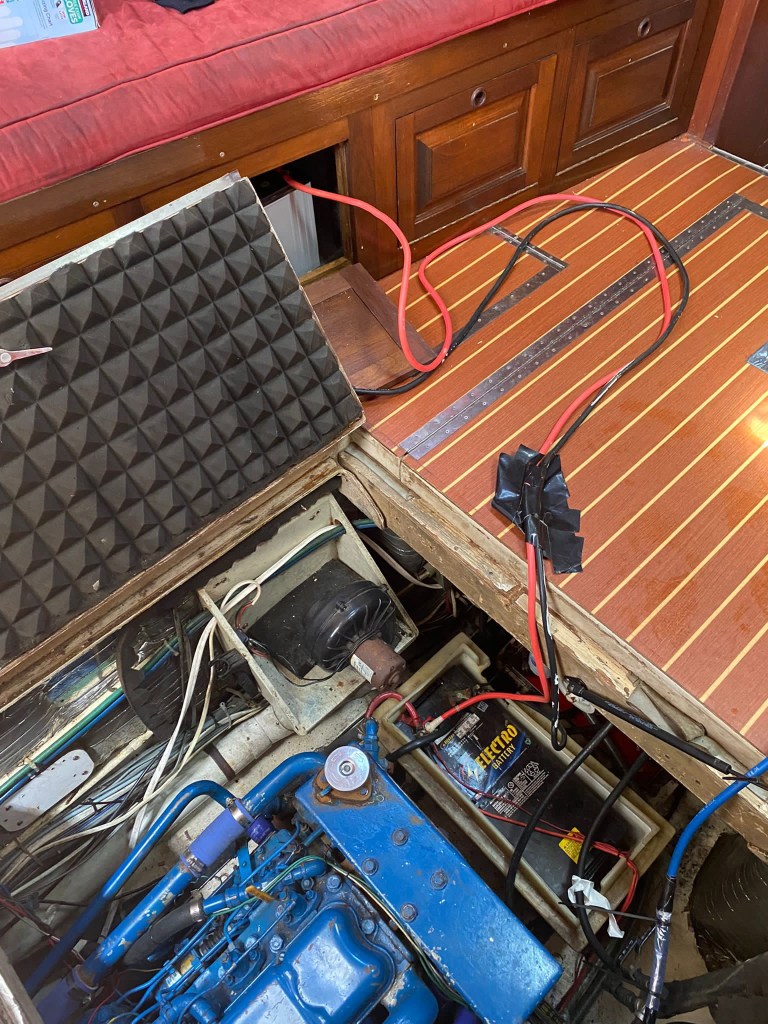

The Fuel Incident a.k.a. Battery incident a.k.a towed into harbour incident

We had a lot of work done to our engine before we departed on the shake down cruise/delivery trip to bring it back from St. Petersburg (Florida, not the Russian one) to Virginia. We needed to have our leaking transmission rebuilt and at the same time the mechanic replaced a lot of the corroded parts in the exhaust and cooling system. While doing this, he commented on the unusual fuel polishing system that a previous owner had installed. As far as he/we could make out, the system was designed such that fuel could be cycled from either tank through one of the pre-filters, whilst the engine and generator are pulling from the other filter. The system is set up such that you select a filter and then both engine and generator will draw from that filter. Either way, whilst looking at the system, he’d shown us how to change the filter (it has a neat little ‘handle’ to ease getting the filter out of the housing), however he’d omitted to mention (as a subsequent mechanic seemed to imply was essential) the need to top up the filter housing with fuel when you’d opened the system.

Before setting off our marina neighbour had regaled us with stories of going through several filters on passage after his boat had been stood for some time. The cause he suggested was gunk in the bottom of the tanks, which whilst quite happy to lay dormant in harbour or under easy sailing, is suddenly shook about by a longer passage inevitably blocking the filters. So, 12 or so hours of motoring later (winds were too light to bother with), once we’d worked out that the alarm making all the racket was a ‘check filter’ alarm, we assumed gunk in the tank had worked its way through to the filters. Only, the filter didn’t look that dirty, but what do we know – it’s a 30 micron filter, maybe the gunk is really small? So we changed the filter and the system seemed to work again, but only for a few hours. On checking the filter again, the filter still didn’t seem dirty, but we were at a loss for what else the problem could be. We pulled into Key West to fill up the tanks in the hope that a greater fresh/dirty(we assume) fuel ratio might help.

Heading out into the Gulf Stream to avoid motoring into a head wind seemed like a sensible decision until we realised just how much water was coming in through the forward portlights. Coming back into the coast and attempting to motor again resulted in the same problem again with the filter alarm. Also, certain on-board systems stopped working, namely wind instruments and GPS. Worrying. Knackered, we found an area of low-ish water and anchored for the night to get some sleep. By now, we’d used about 8 filters and were starting to worry if we had enough filters to get through the trip, we had 6 left at this stage. We decided to change the filters first thing in the morning before moving on but they only lasted half an hour before the alarm sounded again. By this stage, we think, hell, just ignore the alarm, maybe it’s giving a false reading. We carried on for a short while again until the engine died completely. No matter though, we’re a sail boat right, we can just carry on under sail?

Why were we trying to furl the stay sail? Neither of us can remember and the log book isn’t much help either. At this stage, we were both so tired and stressed, that log reading had taken a bit of a back seat. All we can remember is that we couldn’t get the sail to furl neatly, we kept having a scrap of it left out, which was then flogging in the wind. Three attempts and on the third, we’d got the furler, ourhaul and boom topping lift so snarled, with the sail part way out and flogging that we cut the outhaul and brought the sail down. We decided to roll out a bit of headsail instead; there was a lot of wind, but we figured if we just had a bit out, we’d be fine. We were running with a second reef in the main (due to a missing cheek block, there’s no first reef available) and no mizzen sail. This was when we found that we couldn’t tack the boat. Probably in hindsight a mismatch of main to genoa, compounded by a lack of mizzen being set was the cause. Either way, after 3 attempts, we couldn’t get her to go round. Reassessing our options and not wanting to sail backwards along our planned passage route, we nonetheless decided to turn back and head for an anchorage we knew of at Marathon. Furling away the headsail, we decide to use the main to sail onto an anchorage. We didn’t have a lot of choice at this stage as we couldn’t start the engine. This proved challenging as the boat just wouldn’t tack under main alone. We gybed our way across to the anchorage, but losing height on the wind with every gybe, we couldn’t get far enough upwind to make the anchorage. No matter, we decide to head for low water across the channel from the anchorage. It was more exposed but we hoped it would work. This is where we discover that the electronic chart data on our phones was different. The Captain confidently reported 2.4meters of water charted depth, but the sounder was shelving below that. At 1.9m, a confused Skipper compared the two phones (with identical software, and we assumed, charts). The Captain’s phone sure enough showed a flat area at 2.4m for quite an area. The Skippers however showed a knoll with water only to 1.6m. WTF!. Voyager draws 1.65m. Holly crap. We gybed and hoped on heading out to deeper water. The gauge showed 1.7m, but we were heeled over slightly, so maybe… After a few heart stoppers, we were back in ‘relatively’ deep water and dropped the hook. Not inclined to drag in this situation, we put down plenty of chain, about 40m of it and then try to calm down and reassess (the Skipper was pretty unsuccessful on the calming down bit).

It was probably this point that we decided to run the generator, mainly really to see if the fuel problem was isolated to the engine or a wider issue. Having started the generator, we turned on the battery charger and stuck my head under the galley counter to check the reading – Voyager at this stage did not have a working battery monitor. It read 8.4V. Holy crap. We had a dawning realisation that the engine did not charge the house batteries as we assumed it would do. This explained the failing instruments. The generator ran for about half an hour and then failed itself. This was a very low point, we were exhausted both physically and mentally. Being on an anchorage with no working engine or generator, and little to no battery power is not a pleasant situation to be in. Not imagining we’d ever need it, we’d taken out TowUS membership before leaving. The Captain called these guys, but the initial answers were not positive. We needed somewhere to be towed into and the marinas at Marathon where we’d dropped the hook were booked up. For weeks. After a period, the TowUS agent suggested the possibility of space with a small boatyard in Marathon. No guarantee they could take us, but the agent suggested we ring first thing in the morning (New Year’s Eve) and plead our case. I had a very bad night of sleep, seriously doubting whether we’d bought the right boat, or even whether what we were trying to do was a good idea at all.

Setting up for the tow was a little nerve wracking mainly as we weren’t sure how much power was still in the windlass batteries. Didn’t get much sleep thinking about how we could use rope winches to help pull the anchor up. Too much wind to pull the anchor up by hand. Fortunately when Geoff from TowUS turned up, he kindly took the strain off the anchor and thankfully we had enough power left to pull up the anchor using the windlass. Phew!

Geoff had clearly done this job before and expertly towed us into a really narrow channel down to Marathon Marine, who’s guys were already on hand to help manhandle the boat round in their narrow turning pool. One of their guys was on board almost immediately to take a look at our engine. Looking at the filters I’d been changing out, he didn’t think they were dirty and set about bleeding air from engine and generator, which look a long time in both cases. He agreed that the set up with the fuel pump was somewhat crazy and advised us to only have fuel open to either engine or generator at one time, less the running system try to pull fuel through the offline system and in so doing draw air though. In the medium to long term, he suggested just having one filter per generator/engine rather than the selector system.

After a settled couple of days reprovisioning and fixing a couple of minor faults, we on the afternoon of New Years Day 2021. Got about as far as the anchorage area outside Marathon and the engine failed again. Typical. Thankfully, having had some proper tuition on bleeding air, we set about doing that and got the engine going again, though not wanting to chance it, we decided to stay put overnight to confirm that we could get off again in the morning without incident.

The anchor incident

The anchor system on Voyager relies on a locking flap to keep the chain from running out. Looks like it should work fine, though with the swell out in the gulf stream off the keys, somehow, it must have worked loose and the anchor slipped out, just sufficiently so that the anchor could dangle off the bow and with the waves, was pushed up and over the bob stay, wrapping the chain round the metal bar running from the base of the bow to the bowsprit. On having a look, I knew we couldn’t leave it there. With every swell it was lifting off the bar. Not sufficient to free itself, but enough of a lift to make it plain that there was every possibility of it swinging back up into the bow and making a real mess. There’s a few useful items of context at this point:

- Voyager at this stage did not have any Jack Stays run forward. Other than the cleats, there wasn’t anything useful to connect the lines to anyway, which had placed the Jack Stays in the to-do pile of boat work.

- The main anchor on Voyager is 27kg, plus a bit more for the few meters of chain now over the side and dangling round the bar.

- The water line to bowsprit on Voyager is about 7ft, that anchor is a looong way below the deck.

- At time of peering over the edge of the bow, I was 45. Not (too) old, but certainly a lot fatter and a lot less stronger than I was in my 20s when 27kg of anchor would have been airilly lofted out of the water with ease (in my dreams).

- The point at which I decided to clip my lifeline onto the pulpit rail (from lack of anything else suitable) was the point that I noticed that a couple of the rail posts were missing bolts in their bases.

This was the first time in quite a while of sailing where I think I’ve been genuinely scared. Not really from imminent death, the weather was pretty good and though it might have taken Penny a while to come round and pick me up (maneuvering NTL is not easy at best of time, nevermind on your own), the chances of ending up in the water seemed slim. Injury however seemed a lot more likely. Looking down at the chain bouncing on the deck knowing the amount of weight on the end of it, I then looked down at my gloved hands and tried not to think about how easy it would be to get my fingers caught by the chain and what that would do.

Getting the anchor back on board proved exceedingly problematic. Pulling the anchor chain in was possible, but didn’t really help. What needed to happen was the anchor to be lifted over the bar to free it, for which I needed to lift the anchor by the end of its shaft. I very quickly realised that I wasn’t strong enough and I needed help from Penny and to free her up, help from Leo to steer whilst Penny helped me. We managed to get the anchor on board by getting the spinnaker halyard onto the end of the anchor so that Penny could hold some of the weight of the anchor on the spinnaker winch. It meant that I could maneuver the anchor flukes around the bar of the bob stay to free it. Doing so we managed to get in onboard, though even with the help of Penny and the halyard, it was quite a knackering task. The anchors from then on were tied onto the deck, in addition to running through the metal chain latches.

The Forestay Debacle

Snapping a forestay sounds dramatic, but we didn’t hear it go, or particularly see it initially. We had both forestays out and the thing that we noticed first was the forestay flogging slightly, which initially we thought was due to a wind change and the sail needing trimming. Consequently I’d tightened the sheet, which was when I noticed that the sail was bagged out too far to port and realised something was amiss. Walking onto the foredeck confirmed that whilst I couldn’t see the top of the mast clearly, that the foresay must have gone. Next task was to (carefully) roll the genoa away and move the spinnaker halyard to the bow so it could support the mast. We were already sailing with a single reef in, so I took the view that with the sails below the height of the baby-stay that we were ok to keep sailing for a while, though it was clear that our original intent of sailing to Virginia from where we were, which was off the South side of the Florida keys, was not going to work. Fortunately we were only about an hour from being in cell phone range, so started scanning the charts for which marinas to ring. In hindsight we’d have been better anchoring until we’d actually found a rigging firm, but we’re slow learners on that front.

For such a big city and such a great boating area, Miami didn’t seem to be overly serviced with marinas. We went with one who we thought from the phone conversation might be able to help us with our rigging issue. They (like a lot of marinas in the US) advertise as a ‘Full Service Marina’ and assured us that the on-site marine store would be able to help us. I still struggle with the concept of what ‘Full Service’ marina means, because as far as I can make out, it means they might have staff on hand to take your lines, but beyond that, to me they just have things I’d expect in a regular marina. Certainly, services didn’t extend to actually finding a rigging firm, we had to do that ourselves so…

Miami Beach marina also has the novelty of being exposed to the tidal flow of the river that it sits on. Unfortunately for me, whilst I’ve had plenty of experience of getting it wrong on the Hamble or the Medina in the Solent, those experiences are so far in the back of my mind that I’d didn’t really think about the effects of tide in the marina. Foolish boy.

Getting into the first berth was ok (ish). I say first berth because despite having booked, our arrival seemed somewhat of a surprise to the marina staff and the first berth they put us in turned out to have been booked already by someone else. Having intended to go bows in, into the berth that turned out to be a (temporarily) vacant berth next to the one that was double booked, I tried reversing out of the lane having overshot the berth and thus realising that I was actually going sideways, I elected in an instant for reversing into the berth and thus managed to only partly crush the metal BBQ on the Starboard quarter rail.

Foolish mistake number two was to think that the crosswind had been what had sent us sideways. Tide is always (well mostly) stronger than wind. Foolish boy.

So getting into the second berth was more problematic. Now not being entirely stupid (Penny might having something to say about that though…), I had taken account of the wind and had positioned the boat to the windward side of the lane we were motoring into. BUT…I was going too slowly for the cross tide and by the time I actually realised what was happening, we were in the lane and it was too late. Reversing wouldn’t help as we’d still have the issue of parking ourselves against the downstream berths. In the end, moving forward did have a slight advantage as some of the berths were unoccupied. This is important as it turns out that Miami Beach Marina is chock full of expensive Motor Yachts (we got huffily told off from calling them ‘Motor Boats’ and I guess if you’d spent the disastrous sum of money that these shiny things must have cost, then well you might feel a bit miffed being referred to as a mere ‘boat’). Anyway, the vacant berths meant that it was only the starboard rail that managed to wedge itself under the anchor of some very expensive shiny thing, whilst the rest of the starboard side was spared from having a row of new anchor shaped port lights. Another learning point here was to not be carrying the dinghy on its davits when you go into a marina. As we’d ‘parked’ ourselves against the mooring piles, guess what had got tangled up in the pile, yes its those dinghy davit lines. I guess on the bright side, it meant that between the jammed guard rail and jammed dinghy, we were nicely ‘secured’ to the dock. As seems to be reassuringly common in marinas when someone is having a bit of a ‘drama’, helpful folks very quickly appeared to help. Not so much the first guy who turned up and stepped onto the anchor shaft of said shiny thing whose nose we were jammed against as at that point, Penny had her hand in the way trying to free the rail. Still, one slightly crushed hand later, we took a moment to assess our options. My tired/stressed and therefore slightly addled mind thought that we’d be able to walk a mooring rope across to the other side of the lane and use that to pull the bows across. In hindsight, this will have been a huge effort to rig together and probably not very effective in that tide. Helpful person number 2, in addition to not crushing Penny’s hand, suggested just using the bow thruster. I was a bit dubious of this having previously been warned of the inadvisability of running the bow thruster for long periods. I was wrong. Turns out that a sufficiently large bow thruster is a real win and managed to drag us round against the current more easily than I would have ever thought.

Viewed against later rigging experiences, managing to find Nordic Marine in Miami was a stroke of luck as they were excellent. Their guy Jyriki came to see the boat the afternoon we rang and arranged to have the forestay removed the very next day after we explained that we were on our way up the coast. They had the new forestay cut and ready to fix three days later, which was truly excellent work. Getting up to their yard at Hurricane Cove marina was ‘interesting’ as the marina is something like twelve bridges up the Maimi river. I hadn’t realised either that some quite large boats make their way up river. Meeting a (relatively) small container ship coming the other way with two tugs was a bit nerve racking as we had probably a metre to space between the bank and us and then us and the ship. As we approached the bow, we spotted the tug at the stern come into view, see us and then dart backward with his engine in full reverse so that we didn’t get squished by the stern. We were grateful for that, though I still needed a fresh pair of underpants.

Stranded at Fort Pierce

If I ever go into business it’ll be in the rigging business. Not because I know the first thing about it (I can learn!), but because they’re clearly in massive demand. Our hopes of a quick fix evaporated as the firm we called suggested that the earliest that they could make a rigging assessment would be in two week’s time. So, one rental car confirmation later, we were off home to return for their verdict after a couple of weeks. The verdict unfortunately was not good. Our rig was assessed to be a Frankenstein like assortment of cable “from the islands”, most of it manually rather than machine swaged, with many bits that had clearly been extended where they obviously hadn’t had sufficient cable. The tang plates and bolts were assessed to be the originals and given that one of the bolts had already gone, the advice was to replace the lot. We’d assumed when we’d bought the boat that we’d have to replace the standing rigging, but we’d really hoped we could get it back home to Virginia first. Clearly this was going to take a lot longer..

Manufacturing the tang plates took time as did repainting the mast which we’d decided to have done thinking that we may as well since everything was already off the mast, so by the time all this had been completed, we were getting really close to the 6 month point since we’d bought the boat in Florida. Although we’d already paid to extend the period we could keep the boat in Florida before paying sales tax, we really didn’t want to go over the 6 month limit and have to pay Florida tax as it was considerably more than the Virginia sales tax which we’d already paid. Consequently we were really pressurising the rigging firm to finish and we could tell that we were just one of a whole bunch of people trying to get work done. Fortunately the rigging firm were really understanding and were able to get us away before time ran out and we were able to head off for the final leg towards Virginia. Or. So. We. Thought.

Nuts, pins and that damn fuel pump

In hindsight, we really should have used the time in Fort Pierce to sort the fuel system out. Clearly we didn’t, so perhaps rather predictably for you reading, not long after leaving Fort Pierce the fuel pump was back to its old tricks of the alarm going off about half an hour after we’d been running engine or generator. We thought we could just keep the filters topped off and that would keep things going ok. Clearly not, about half an hour was the best we could get before we had to stop, take the filters apart, refill with fuel and try again. But hey, we’re on a sail boat, who needs an engine right? Oh, how naive.

In the meantime, a second problem decided to surface. Obviously at night, because if anything’s going to go wrong it’ll happen when you can’t see. Penny was about to go off watch, but said that the boat wasn’t responding to the wheel, so the skipper confidently stepped in assuming that he could sort out the issue. Oh how misguided. It was very quickly obvious that the wheel was no longer connected to anything. After a slight(!) panic in thinking that the cable had parted, we found that the nut at the end of the bolt attaching the cable to the rudder quadrant had simply wound off and released the cable. That’s a quick, easy fix right? Wrong! Having removed the mattress from the aft berth we spent quite some time staring at the quadrant, which, unencumbered by a steering cable, was merrily swinging back and forth with the swell on the rudder. Though the fix was pretty obvious, the trick seemed to be how to manage it without crushing your fingers as the quadrant slammed against the metal frame, a prospect neither of us particularly fancied.

Fortunately a forward thinking previous owner had taped the emergency tiller to the metal frame we were both peering over. After a certain ‘doh’ moment, the tiller was freed from its tape and quickly assembled. It’s at this point we discovered why it’s an emergency tiller and not a ‘hey I fitted an alternative if you get bored with the wheel’ tiller. Steering with that was, to massively understate, tricky. The tiller extended up through the aft cabin hatch (clever, huh?) and the best method we found was to brace your feet against the inside of the hatch and lean back on the tiller as hard as you could. Your dearly beloved then puts her nimble hands in the way and tries to fit the nut back on whilst you put your back into it and try to hold the damn thing steady. A mere 3 hours start to finish I think and really not stressful at all, I’d really recommend it if you find yourself at a loose end of an evening.

The very next day we were merrilly following the Gulf Stream on a sunny day in moderate winds with a moderate swell. Champagne sailing. With the wind from the North East we were having to tack to keep ourselves in the middle of the stream to maximise our boat speed. With a full genoa out on one of these tacks, the sail caught at the spreader and try as we might, we couldn’t free it. Eventually, it tore free, which was annoying that we’d ripped the sail, but relief that we’d freed it. The relief didn’t last long at all. We very quickly realised that the sail had caught on the split pin which kept the clevis pin in place, which in turn connected the upper part of the cap shroud to the lower. Any sailor will appreciate the sense of deep shit seeing this will cause. The cap shroud is the thickest of the standing rigging cables and the main cable providing lateral support to the mast. Losing that is a big deal. We (very) gingerly lowered the sails and supported the mast with the spinnaker halyard. Time to look for (another) safe harbour.

At this point we were around 120 miles off the coast, about a day away from safety.

Do you remember the fuel pump? Time for it to make another highly irritating reappearance. By this stage, the pump was really refusing to play ball, barely giving us 5 minutes before alarming. After many, many tries of killing the engine, switching the pump between filters and restarting we were getting quite frustrated. So…we disconnected the alarm. I know what you’re thinking, genius huh? The engine actually ran for about half an hour after this and for a little while we half thought that maybe it was just a dodgy alarm sensor in the pump. Wrong. Eventually the engine coughed and died. No amount of attacking the lift pump seemed to get any fuel through. A different approach was required. So we had a cup of tea. Tea fixes everything.

Whilst drinking our tea, we contemplated our position and wondered for how long we could gently drift along in the Gulf Stream and where we might end up if we did. This didn’t feel particularly life threatening and we suspected that if we triggered our EPIRB, some kind soul might appear to pick us up. We doubted however they’d be quite so happy to tow Voyager the 100+ miles back to shore, at least not without a considerable financial incentive to do so. I should point out here that whilst both of us have completed our Diesel Engine Maintenance course we are absolutely not mechanics, so the knowledge of how to change a raw water impeller wasn’t particularly useful at this point. We did wonder whether it might be a fuel line blockage rather than the pump, so the sensible thing seemed to be to try and bypass the whole lot. Spare fuel line on board at this point would have been useful, but we didn’t have any and the line between the engine and the fuel pump wouldn’t reach as far as the tank.

To extend the line therefore we cut away at part of the lines for the fuel polishing system, thinking that as that hadn’t been used, the lines might be clearer. Trouble is, we didn’t have any fuel line connectors, so the ‘solution’ was to abut the two lines, duct tape them together, cover with a plastic bag, zip tie and add more duct tape. And hope. Not that I can believe I am admitting this, we then drilled a hole into the top of the starboard fuel tank and pushed the line in. Miraculously, this worked and allowed us to start heading to the nearest marina in Georgetown GA for us to reassess. [This ‘solution’ caused us plenty of problems later on of which more later]

Oh, also at this point, the batteries died. Remember that our batteries don’t charge from the engine alternator? Well, bypassing the fuel system was fine for the engine, but we still couldn’t run the generator. No generator, no battery charging. With no spare cable on board, I disconnected the cables feeding one of the electric heads so that we could take a house battery in turn and parallel it to the engine battery to allow it to charge. Which was yet another couple of hours of hot sweaty work to disconnect and reconnect cables (I may have had a little cry at that point…)

All swell till the fuel line separates

Having made it to the marina in Georgetown, we made a call to the rigging firm who were excellent and agreed to have someone take a look at our cap shroud at the start of the next week. We were keen to get going again and conscious that the marina we were at in Georgetown only had a maximum one month stay time for transits. We did try to get a mechanic to have a look at our bodge job of a fuel line, but were unable to find anyone who could help. Either too busy in the time we had available, or couldn’t get new fuel line in the available time (an excuse I’m a little sceptical of, having subsequently bought my own fuel lines off Amazon…).

Given the length of the river at Georgetown to get to open water we’d opted to leave at the turn of the flood tide, so the ebb would give us a speed boost on the 15 of so miles to get out. About 1 mile from the river entrance, the engine died. We’re so used to this now, we nonchalantly dropped the hook and waited while the boat swung round into the flow of the river. There was quite a rate of tide, but thankfully the anchor held and we were able to investigate. Turns out that whilst duct tape might work as a temporary fix, it’s really not a long term option. The adhesive under the tape had turned to warm gloop and the pipes had just slid apart. We always carry a spare can of fuel, so rather than try to re-do the ‘bodge fix’ we just stuck the pipe from the engine in the spare fuel can (which we lodged under the galley sink), bled the air from the engine and carried on out of the river. We’d figured that once out of the river, we’d set sail and all would be well. The engine did seem to be drinking through our fuel can alarmingly quickly which should have prompted additional questions, but with the blissful ignorance of non-mechanics, we just carried on until some time later when this really bit us and we figured out why.

Who needs power anyway?

The sailing was going great, but we still had this crazy set up which allowed us to charge the house batteries from the engine alternator rather than the generator which wasn’t working. Because the fuel in the starboard tank seemed fine and because we thought the fuel in the port tank might be suspect, we stripped out the fuel supply line from the starboard tank and connected the engine to the fuel in the starboard tank via the hole we’d previously drilled, but a single whole line rather than with the bodge. About a day away from Georgetown when we wanted to start the engine to charge the batteries, we just couldn’t start the engine. Doing all the normal measures to bleed air from the engine we were dismayed to see bubble of white gloopy goo coming out from near the fuel injectors. We quickly realised that as the fuel lines were coming apart on the way down the river from Georgetown, the melting adhesive under the duct tape must have worked its way into the engine. Thankfully we had spare engine primary fuel filters and in taking the old one off, the fuel inside was just swimming with white globules. Even after fitting the new filter, it took an absolute age of tentatively running the starter motor to clear all of the gloop up to the injectors. We probably spent 3 hours trying to start the motor, though it thankfully did start in the end. In retrospect, we were probably extremely lucky that it started at all and that we didn’t permanently gunk up the injector heads. So if anyone reading had thought our fuel line fix was a clever one, it really, really wasn’t.

Surf the beach

Voyager has fuel gauges, but they don’t work (you really didn’t think they would, surely?), so one of the advantages of a hole in the top of your fuel tank is that you can see approximately how much fuel is left in the tank. As we’d experienced when using the fuel can, we’d observed that the fuel was disappearing alarmingly fast and by using the fuel level sender as a dipstick, we were able to confirm that we only had a few gallons left. So much was our concern that we’d decided that we needed to head in to shore for a fuel dock as soon as we could. From a scan of the charts, we’d decided to try for Bogue Inlet. It looked to have 7ft of water at the entrance and with Voyager drawing 5.5ft, we hoped this would be ok. Unfortunately, there was a real swell on as we approached where we thought the inlet entrance should be, with some big breaking waves which we quickly realized were higher than the 1.5ft of clear depth we thought we had to play with. Getting very cold feet at this stage, we decided to turn back, though in hindsight backing directly out might have been the smarter move. Turning to port however in what was a narrow channel had the effect of reducing the depth further so that as the next wave trough went past, with an almighty bang, our keel stoved straight into the beach. Very fortunately the next wave peak picked us back up again and by gunning the engine, we were able to get back out to deeper water. Beach surfing in an Irwin 52? Not a recommended activity I’m afraid.

But where does the fuel return to?

With slightly frayed nerves, we realised our best (only) option for fuel would be Morehead City, but we were pretty confident that we didn’t really have the fuel to get there. Reluctantly we decided to see what fuel was in the Port tank as even though we’d been assuming that the fuel might be bad, it seemed like our only option. On Voyager the port tank is harder to get to than the starboard and requires removal of some of the seating. Having removed the seating and lifted out the fuel sender to have a look inside (no working gauges remember), the port tank was full to the brim with fuel. This initially didn’t make any sense at all, we’d previously been using the tank and hadn’t filled it since Key West, so there was no way it should have been full, unless…

In a mistake that will be blindingly obvious to anyone mechanically minded but the skippers had simply missed, whilst fuel was being drawn from the starboard tank, the fuel return was set to the port tank. Though Voyager’s Perkins diesel engine burns around 1gal/3.8L an hour, it sucks quite a bit more than that through the filter and back to the tank, which is fine, if the fuel is being returned to the right tank…

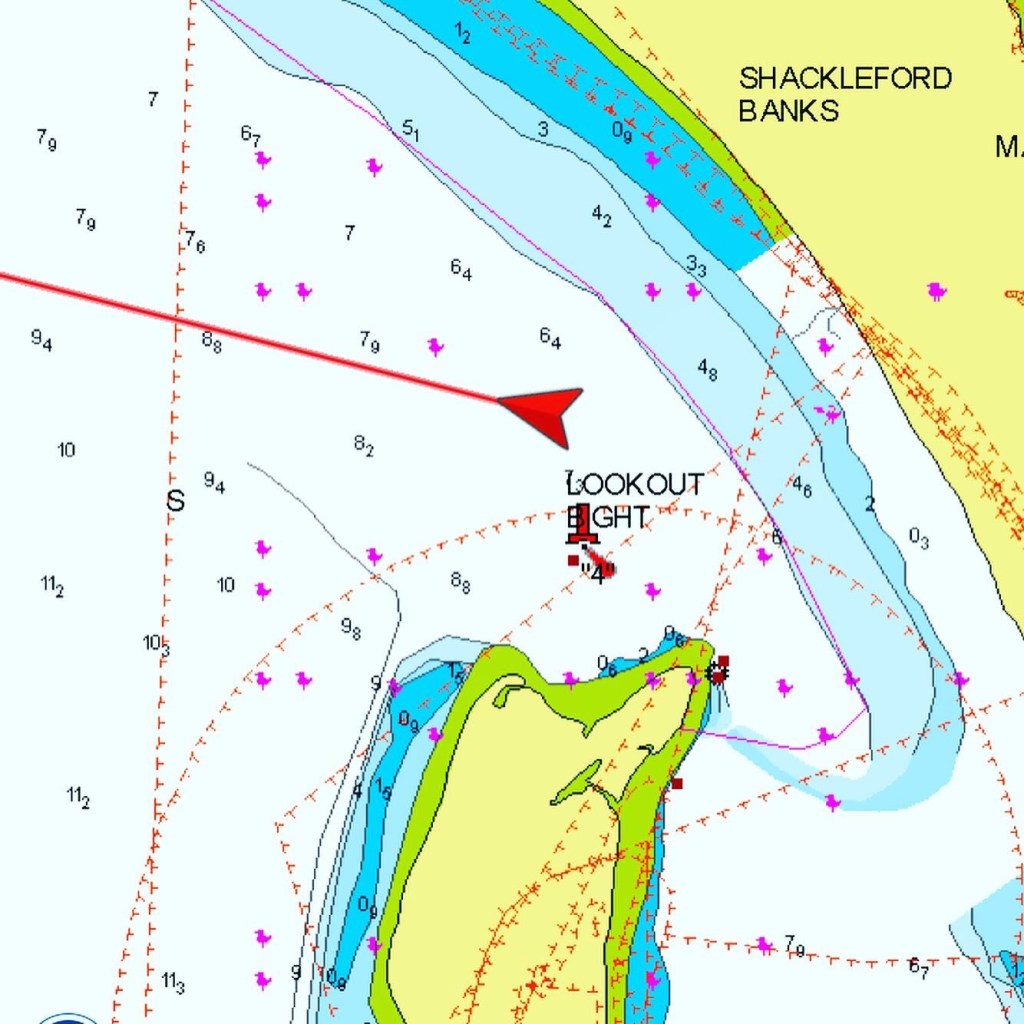

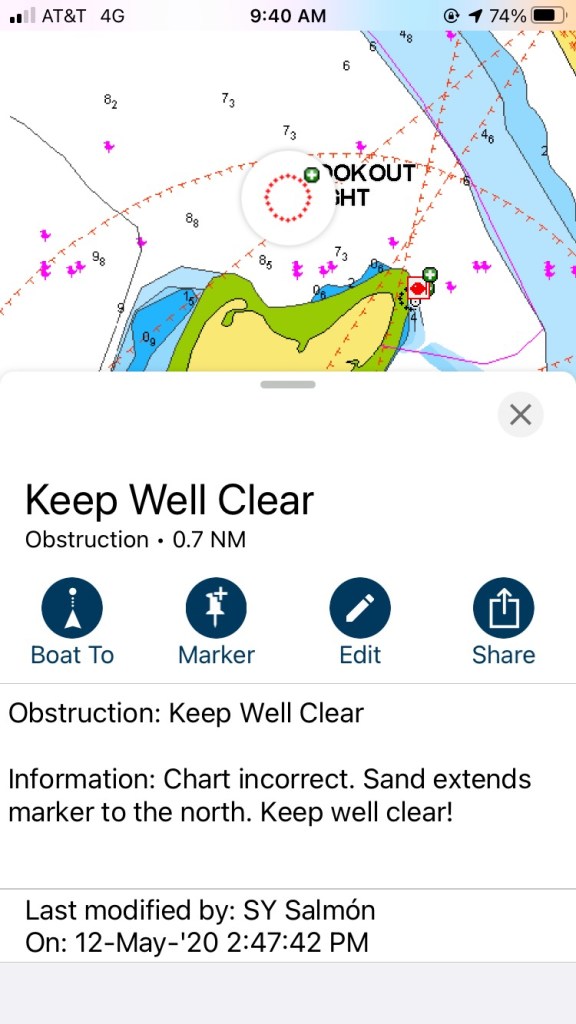

Read the charts

Having realised that our fuel situation was not as dire as we’d initially thought, we decided to anchor overnight at Cape Lookout before heading back to Morehead City the following day. Dusk was falling as we approached the anchorage and we could make out several anchor lights already there. The entrance to the inlet had a starboard lateral mark which looked to be about a cable out from the head land with water all round. Being late, the overly confident Skipper decided to duck inside the bouy, much to the protestations of the more sensible Captain. It wasn’t until the Coxswain shouted out ‘I can hear waves crashing’ that the skipper fortunately backed off the throttle as Voyager ploughed a furrow up the second beach in two days. Mercifully the Skipper’s blushes were spared as with some forceful use of reverse managed to pull the boat back out into deeper water. Closer inspection of the electronic charts showed a note at a lower level of zoom: ‘Obstruction: Keep well clear. Sand extends’. I think we managed to confirm that. Exiting the anchorage the next day and seeing the buoy fully dried out on a sandbar reinforced the salutary lesson that even if the chart does show 7 meters of water, you may just want to double check. Either that or perhaps just listen to the Captain.

Nobody died

The remainder of the deliver trip was unremarkable. We filled up in Morehead City as planned, had a very pleasant sail around the notorious Cape Hatteras and were in our temporary home berth at Gloucester Point a couple of days later. Judged against the Skipper’s basic performance criteria of ‘zero death’, the trip was agreed to be a stonking success…