So who is this ship called Voyager, why did we buy her and why did we name her Voyager anyway?

TL:DR

Voyager is an 1980 Mk1 Irwin 52. We bought her because she was in the budget we had and she had separate cabins for the kids (if you have teenage boys you’ll understand). Previous name was not age appropriate so we needed to change it and Voyager seemed to fit, plus the skipper has some (possibly irrational) aversions to witty boat names, so…

IRWIN

Irwin yachts were the mastermind of Ted Irwin, a Florida based racing yachtsman and boat designer who founded the Irwin Yacht & Marine Corporation in 1966. The firm began building the Irwin 52s in 1976 with the design being updated to a Mk.II in 1982 and then replaced by the Irwin 54 in 1988. Over 250 Irwin 52 hulls were launched in that time. They were built with the Caribbean charter and cruising market in mind and hence came with a lifting keel with a keel up draft of 5ft 6in (1.65m). The standard layout in the Mk.1 52 is a v-berth up in the bow, a bunk cabin to starboard by the main mast with a head opposite. Centrally is a large deck saloon with an aft facing chart table to port and a step down to a galley to starboard. Continuing aft is an area variously used as seating, storage or an additional berth. Finally there is a large aft master cabin with a thwart-ship double berth and an en-suite head.

Why buy a 52?

Any boat purchase is a compromise of priorities within your available budget and we’re no different here. We had a purchase price budget of around $130,000, which sounds like a huge amount of cash, until you look at the criteria of what we were looking for, after which your options narrow very quickly. So cutting to the chase, what were our priorities:

1. Interior space.

Ultimately we’ve got to live long term on this thing, so we were always looking for a house with sails, rather than a sailing machine with an austere interior. Not that we were necessarily looking for shiny or plush, we can fix that, but available living space is something you’re stuck with once you’ve bought it. Primary above all other considerations here was separate cabins for our two boys. No matter how well they get on, we figured that teenagers with no personal space would be the fastest route to misery and failure of the whole plan.

I’d state up front here that whilst catamarans would have absolutely met this criteria and then some, cost ruled them out for us right from the get go.

There are a number of yachts that have a fore-berth and a cabin formed from a passageway to the aft cabin. We seriously considered a few of these, with Moody 422s and 425s being the main ones we looked at. What we liked about the Irwin 52 was that the bunk cabin is forward by the mast and therefore not in a corridor and so for a teenager, still their own private space rather than a thoroughfare.

Other pluses for the Irwin 52 for us were the two heads, the galley, the large dedicated chart table and the huge headroom in the aft cabin.

A few of the boats we’d looked at had their galley’s as part of the passage

way to the aft part of the boat. We liked the fact that the Irwin 52 has a

large galley, but one where you’re out of the way from the rest of the crew, so

no one has to dance around whoever’s cooking to move around the boat.

The Irwin 52s have a stepped deck such that the aft deck is maybe a foot

above the foredeck (must measure that…). Clearly a stepped deck must be a

heinous crime as no modern yacht manufacturers do this. Maybe its because they

think people will trip over it which seems really odd as there is typically so

much to trip over on a boat anyway, adding one more thing doesn’t seem it would

make much of a difference.

Firstly, though the Captain appreciates a fine cut of jib as much as the

next red-bloodied lady, that’s by no means a deal-breaker (just look at who she

married…) and the Skipper would be happy in a bath-tub as long as it had a

sail.

Thirdly with the stepped design, the Irwins also have really deep gunnels on

the foredeck which is both extremely useful to brace your foot against.

2. Hull safety

Safety of the hull, what on earth are you talking about? Well, a lot of safety things (liferafts, lifelines, bouys etc) can be added but you can’t do much to change the shape of the hull. Ideally we were looking for a full keel built as part of the yacht superstructure and a skeg mounted rudder. Our concern here is two-fold. Firstly, we knew that the type of sailing we would do would have us going into remote anchorages that may not be accurately charted. In other words, we knew that the chances of running out of water would be an occupational hazard. This has since proved an accurate assumption on several occasions (two chart malfunctions (ahem) and one where we knew we were chancing it, decided against, but turned around rather than backing out and hence turned out of the channel and onto the beach – oops). We also knew that because of the priorities of interior space we’d be in the market for an older boat. That’s not to say that bolted keels aren’t safe, but in an older boat which may or may not have run aground several times, we felt we’d sleep better knowing that there was no way that the thing holding the boat upright could come off. Google Cheeki Rafiki and you’ll maybe see what we mean.

A skeg hung rudder was a related concern in that in the (hopefully) unlikely chance of hitting any ocean debris/marine wildlife (not intetionally obviously, more an observation that Orcas seen to have developed an interest in yachts off the coast of Spain), the skeg should support the rudder and prevent loosing it.

3. Sailability

Voyager does not have a sail set up that we would have chosen if that factor was higher than our third (and lowest) priority. At purchase, it had no light wind sails, no spinnaker pole, no boom vang, the topping lift is a fixed wire, the running backstays make gybing a lengthy process, not much is run back to the cockpit in terms of sail controls and the staysail is a self tacking one, making heaving to difficult unless you’re just under the genoa.

However, having now spent a while sailing her, we do like the flexibility that the staysail and mizzen gives us to run with just those two set in a ‘jib and jigger’ set up in heavier winds.

The rest we may (or may not…) look to update or change as we go along. Given the ‘house with sails’ requirement and the fact that we’re to cruise to places, not to race there meant that we were happy to make the compromises in this area.

What’s in a name?

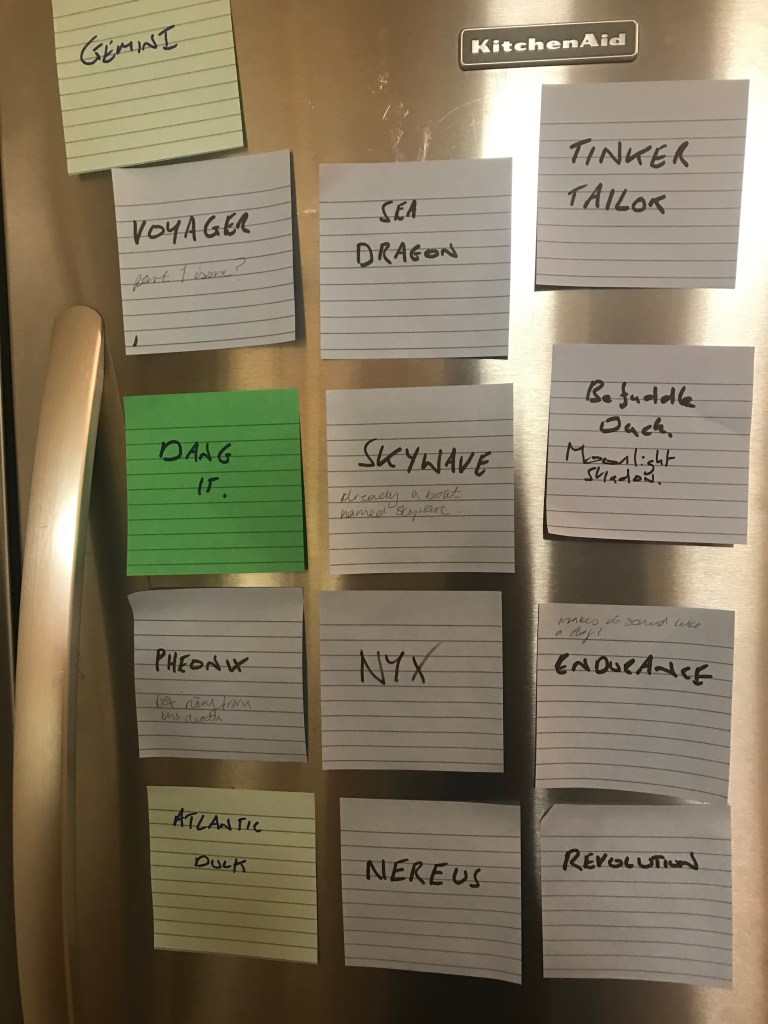

Voyager was originally named Sailaway (maybe not all the way from purchase, but certainly for a very long time). When we came to buy her, the previous owners had named her ‘No Tan Lines’, which is highly appropriate for sunny Florida, but less so for the ‘naked boat’ connotations of sailing with kids, so it had to go. This is where we found agreeing a new name for the boat to be harder than naming our children. Broadly ‘we’ (the skipper) felt that the name had to meet the following criteria:

1. Can you use it on a ‘May Day’ call?

Yes, obviously you can use your callsign on a MayDay (if you can remember it!), but it’s easier to use the boats name and it really helps if the name is: short, easy to understand and not a distraction from the seriousness of the situation. This is dreadfully boring and even more so if you’re really expecting to end up in a ‘MayDay’ situation. However if you’re planning to go into foreign ports, it helps if your boat name isn’t likely to offend or cause derision with the port officials (even going into the marina in Miami, the marina staff laughed when we announced ourselves as No Tan Lines). Witty boat names are a lot of fun, but we felt that whilst that works for bobbing about around your home port, it didn’t really suit international travel. Gosh, I’m boring myself just writing this…

2. Does it fit the boat?

Voyager is not a lithe spritely racy thing, so any names implying that just wouldn’t suit. She is a large, heavy, slow thing that is built for long distance travel. Though we spent ages going round many other names, Voyager ultimately stuck for us.